A new function of liver vascular cells discovered by IIMCB scientists

Scientists from the International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Warsaw (IIMCB), in collaboration with researchers from the theMossakowski Medical Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences, other institutions in Poland, and partners from Germany and Denmark, have discovered a new function of specialized liver endothelial cells (LSECs). In their latest study, published in EMBO Reports, they demonstrate that LSECs actively remove free hemoglobin. This discovery changes our understanding of how the body handles hemoglobin after the breakdown of red blood cells and opens new questions about the importance of this process in hemolytic diseases and liver disorders.

Hemoglobin is a protein responsible for oxygen transport in red blood cells. Under physiological conditions, it is released in the spleen when a small fraction of ageing red blood cells rupture instead of being removed by macrophages – immune cells that act as the body’s “clean-up crew”.

In certain diseases, red blood cells are more prone to damage, leading to much higher levels of free hemoglobin, which can have harmful effects. Until now, macrophages were thought to be primarily responsible for clearing free hemoglobin. However, the EMBO Reports publication shows that specialized LSECs (liver sinusoidal endothelial cells) also play an effective role in its removal.

The liver captures hemoglobin: the key role of LSECs

LSECs have long attracted the attention of biologists because they function as a highly efficient blood “filter”, capturing circulating molecules that may be harmful. They also play an important, albeit indirect, role in regulating iron metabolism. In response to iron overload, they initiate signals that limit its release into the bloodstream.

The IIMCB team has shown that these two known functions converge in a newly identified role: LSECs can actively take up free hemoglobin and trigger processes that enable its safe degradation, while simultaneously supporting the maintenance of iron balance in the body.

Scientists from three countries track free hemoglobin

As emphasized by Dr. Katarzyna Mleczko-Sanecka, head of the Laboratory of Iron Homeostasis at IIMCB and corresponding author of the publication, the impulse for the study came from observations made by researchers at the Mossakowski Medical Research Institute (IMDiK PAN). They noticed that after macrophage depletion in mice, a substantial amount of free hemoglobin was still transported to the liver.

“They asked us to interpret this observation. The topic immediately struck us as particularly important and directed our attention to LSECs, which we had previously studied in the context of iron homeostasis. The observation made by our colleagues at IMDiK initiated this project and several years of very fruitful collaboration between our teams,” the researcher explains.

Research groups from Aarhus University (Denmark) and the Leipzig University Medical Center (Germany) also contributed to the success of the study. Collaboration with the Leipzig center enabled the authors to use human liver cells, allowing them to assess whether the mechanisms observed in mice are also present in humans. Researchers from the Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics PAS, the Maria Skłodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, and the International Institute of Molecular Mechanisms and Machines PAS also played an important role in the project.

The IIMCB team that described a new function of LSEC cells. The photograph shows, among others, the co–first authors of the study: Dr. Aneta Jończy (first from the left) and Dr. Gabriela Żurawska (first from the right), together with the corresponding author and head of the Laboratory of Iron Homeostasis, Dr. Katarzyna Mleczko-Sanecka (second from the right).

The IIMCB team that described a new function of LSEC cells. The photograph shows, among others, the co–first authors of the study: Dr. Aneta Jończy (first from the left) and Dr. Gabriela Żurawska (first from the right), together with the corresponding author and head of the Laboratory of Iron Homeostasis, Dr. Katarzyna Mleczko-Sanecka (second from the right).

From proteomics to the “Eureka!” moment: how LSECs revealed their new role

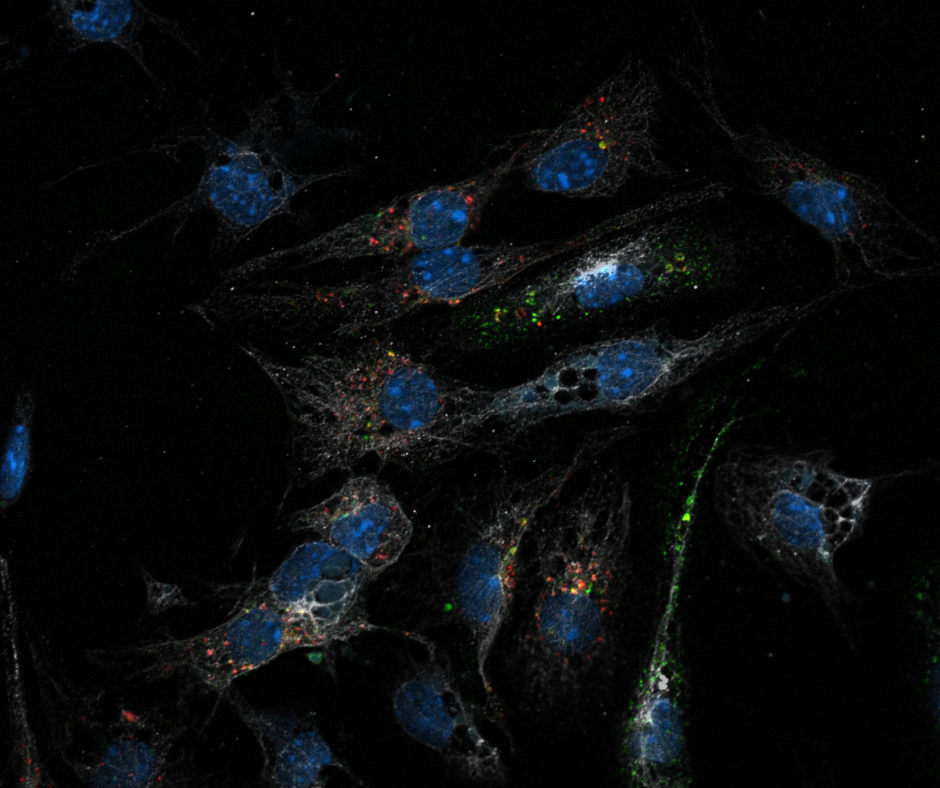

The study employed state-of-the-art research methods, some of which were available through the comprehensive IN-MOL-CELL infrastructure. These included flow cytometry, cell imaging using confocal microscopy, proteomics (analysis of all proteins present in a cell), and spectroscopic methods to measure iron levels in cells.

A breakthrough came with the global analysis of all proteins present in LSECs and their comparison with vascular cells from other organs as well as with macrophages.

“It turned out that in many respects LSECs resemble macrophages more closely than their endothelial counterparts in other tissues, which strongly pointed to their new role in iron recycling,” recalls Dr. Katarzyna Mleczko-Sanecka.

A particularly satisfying result for the researcher came from an experiment in which aged red blood cells – normally directed mainly to the spleen – were administered to mice. The team then examined what happened in liver vascular cells. Out of thousands of analyzed proteins, only five showed changes in abundance, including the two main hemoglobin subunits.

“This was the moment when we clearly saw that hemoglobin released in the spleen reaches the liver and is ‘eaten’ by LSECs,” adds the head of the Laboratory of Iron Homeostasis.

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells drive hemoglobin clearance.

Scope for further research

IIMCB scientists stress that their study does not constitute a ready-to-use therapy but rather describes a new biological mechanism and sets directions for further experimental and clinical research.

The finding that LSECs act as an important hemoglobin filter raises questions about whether, in hemolytic diseases, excess free hemoglobin may overload these cells and impair their other key functions. It also prompts consideration of the extent to which LSEC activity in these conditions may protect other tissues by capturing excess hemoglobin. At the same time, an important question remains as to whether, in liver diseases, the capacity of LSECs to clear hemoglobin is compromised and what consequences this may have for the entire organism.

Research areas that may benefit from the findings reported in EMBO REPORTS:

-

- Hematology

- Liver biology

- Research on hemolytic diseases

- Medicine (iron metabolism disorders

The publication “Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells constitute a major route for hemoglobin clearance” is available here:Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells constitute a major route for hemoglobin clearance | EMBO Reports | Springer Nature Link

The study was funded by the National Science Centre (Poland), grant no. 2018/31/B/NZ4/03676.